Which You'll Either Displace, Be Divested of, or Read to Demolition

I have heard tell of the legendary work of fiction that is Good Omens. Yet, while I knew the basic premise of the plot and was aware of its massive fan-base, it was not these things that had first reached me.

The first time the infamous reputation of Good Omens entered my awareness it was on a post online which discussed the book's notorious reputation for being stolen. The writer rued the amount of copies they had had to purchase in order to replace those that been regrettably lent to a friend who, naturally, neglected to return it.

One might ask why the unfortunate soul continued to lend their precious copies of the novel to people, repeatedly not learning from their mistake.

It could well be that the book, in a nefarious effort be read by as many irreproachable readers as possible, simply wanted to leave its former master. Perhaps the master himself (the book's original owner) had become so possessed by its wicked humour, masterful plot, and clever devils that they were at the mercy of its will.

Or, conceivably, the book may just be that good.

I later heard of other strange habits the book had acquired. Apparently, the novel has a nearly diabolical way of turning strange shades of brown, being dropped in the bath, or totally falling apart at the spine so that it must later be carried in a plastic bag like a dead thing.

I certainly do not think that any of this is the author's fault, both of whom I much admire. Unless of course, somewhere along the way, a curse of destruction was placed on it in a ploy to sell as many copies as possible.

The book's foreword, however, will tell you about the author's puzzlement at the state of some of these books which they later find themselves signing, as if taking credit for the disheveled thing in some ironic way. So, unless we are to accuse them of lying, one can only assume the books bedevilment is a thing entirely separate of them.

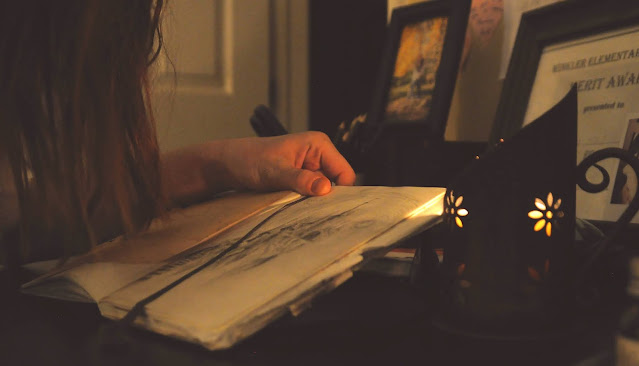

I was cautious when reading the book. I did not take any baths with it. I kept my tea at a safe distance. I made sure to keep it far away from open flames, especially when leaving the thing unattended in the same room as my scented candles.

Yet as I read Good Omens I quickly realized that no amount of caution was enough as not long after beginning the thing my copy literary started to skin itself alive, like some sort of snake.

It began slowly at first, and though I made sure not to pick at its dead skin, trying hard to avoid touching it at all, every time I took up the thing the damage seemed to have only gotten worse.

Meanwhile, the cheeky little devil on the cover looked so cocky and calculated that I found I quite mistrusted him. I certainly had not heard him on radio 4, though he kept telling me that I had. Perhaps I need to start paying closer attention when Freddie Mercury comes on.

I finished the novel late one Thursday night, exhaustion looming over my head. I thought it would be the end of it all then, as there were no obvious stains or tears beyond the continual shedding of its plastic skin, when, to my own surprise, I received a confession that made it all click into place.

It could not have been closer to the end of the book even if it had tried. Luckily, I read every word, down to the author's bios in the back. Terry Pratchett went last, relating from beyond the grave that "P.S. (Neil) really, really likes it if you ask him to sign your battered, treasured copy of Good Omens that has been dropped in the tub at least once and is now held together with very old, yellowing transparent tape."

Pratchett, you sneaky bastard. It all makes sense now.

These were my first thoughts as I read those words. Then, before I knew what I was doing, I went online and ordered myself some clear book-tape.

Only the best for the best, that's what I say; and if Neil likes it this way, who am I not to oblige?