:And its Icky and Intimate Parts ad Portrayed in"The Time Traveler's Wife"

The time and place in which we read a book is hardly inconsequential to our perception of it.

I first read The Time Traveler's Wife when I was a young girl. In many ways, I was too young to understand the novel.

There is some perfect irony in this, I think. As I reread the novel for the second time, I realized things I had not before. I saw and understood the novel on a level that was far more personal. It was both more familiar and more disturbing than it was to the mind of my younger self.

The novel's protagonist Clare experiences this same sensation within her own story. She meets her husband at the young age of 6 when he appears naked in the front yard of her house. Her husband Henry, a man who suffers from a disorder that helplessly displaces him in time (also causing him to leave anything material and otherwise behind, including his clothes), will not meet her until he is 28 and she is 20.

Naturally, there are some things that Clare at the age of 6 did not understand about the strange time traveler who appeared for fragments in the meadow near her home. He is in many ways a perfect stranger with whom she slowly becomes perfectly familiar, first from the perspective of a child with an innocent crush, and then from that of a teenager who has other more sensational things on her mind.

Rereading The Time Traveler's Wife now I realized that in reading this as a young imaginative girl I had dubbed it a mere romance. Thus, it lost both its strangeness and its ordinariness. Now I realize that this is not the story of two people who come together, bound by destiny and love. Neither is this a story of science fiction, the tale of a time traveler with a disorder made real in its fictional limits.

This is the narrative of Henry and Clare who find themselves together from the start of the story, and though their lives are bound ever since that day when Clare was young and pink and innocent, they are constantly being separated, by time and space, and by each other.

The imagery bestowed to the second part of the novel, titled a drop of blood in a bowl of milk, paints the perfect picture of how this novel makes one feel. There is both an ickyness and an intimacy to the image; for marriage, while beautiful and intimate, has its icky parts too. The bowl of milk in this portrait is something soft and pale and usually untouched, though nonetheless it is spoiled by a small drop of blood. In the same way, Henry and Clare's marriage is stained over time by grief, by frustration, and resentment, by an irritation with the things that keep them apart, and so an irritation with one-another.

Love stories often forget how ugly marriage can be. It is lovely to dream of first kisses, of wedding days, and white dresses, and the perfect romance of two people finding each other in a chaotic world. But when stubbornness and dissatisfaction sears and scars a once white and perfect thing, it is easy to forget the purity it once held.

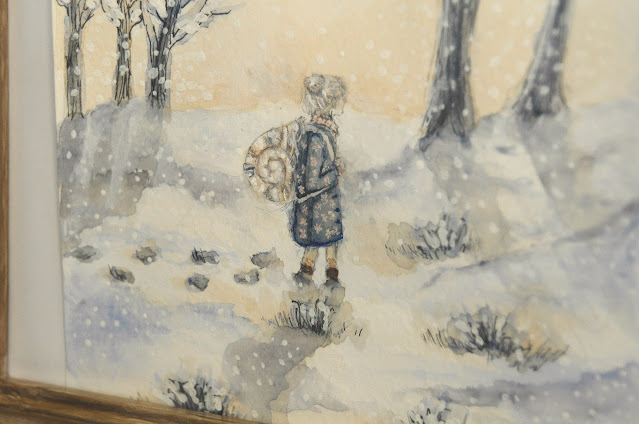

In the end it is those images that linger; these are the details that make the novel memorable: the seared gaze of a grief stricken widower, eye whites shot and yellowed by excessive drinking; the red smudged lips of a woman discarded by love committing suicide alone in her apartment; glimpses of white bloodied sheets stained by miscarriage; blurry pictures of white crystal snow sullied with the blood of a deceased lover; all reinterpretations of that spoiled bowl of milk painted into its type-scripted pages.

The Time Traveler's Wife is a portrait of marriage, as raw and unflattering as it is idealized and filtered by fiction; and it is painted in milk and old spilled blood. It leaves neither out. Beginning with a perfect meadow and Clare in white knee socks, it shy's not from love's icky, messy, and gruesome parts by continually staining perfect white things with red and yellow blotches.

It is a strange way to depict a marriage. Despite its elements of science fiction and literally disordered timeline, their marriage feels doggedly raw, at times as passionate as it is tedious and frustrating. But that is not the strange part: the strange part is that it is its un-ordinary details, its time travel and thus its disjointed and dislocated lives, that makes this marriage feel at all true and real.

After all, it is not only Henry's strange genetic disorder that keeps them apart. At times, it is their stubbornness. Sometimes, it is their own grief or personal lack, an internal dissatisfaction not even their supposedly perfect love can fulfill.

Instead of locking himself in his study or going for a drive, Henry simply disappears entirely, escaping to some other time and space. Time

travel is simply the medium, the perpetrator that makes an emotional

separation literal in their marriage. In reality, such things are not

necessary.

Clare, like myself, once thought that getting to Henry would be the end of it; the happily ever after, not in the sense that this is the end of their story, but in the sense that, in everything that comes after, they could be happy.

This, of course, is not the case. Clare's deepest hurts and hardest times come after. She wept once about how lonely it was to wait for Henry. But this was before, when she still knew he would come and she still had the list he gave her telling her exactly when he would return. Later, she has only the unfilled clothing he leaves behind, and the empty time spent waiting and not knowing when he will return to her.

I myself used to think that being married meant that one never had to be lonely again. It wasn't that I actively believed this, but it was a coming disillusionment I sometimes faced snippets of. I remember a friend once telling me how lonely she was finding marriage to be. I tried not to think about it. Who wants to believe there is no perfect cure for loneliness, after all.

In this way, Clare doesn't learn what it is to be lonely until she is separated from he who is closest to her, not just by time and space, but by personal stubbornness, by internal struggles, and often trivial frustrations.

Sometimes the space across one's bed feels further than time and space. Sometimes one feels as separated from their spouse as if they were a perfect stranger.

But that is what marriage is about, is it not? Not that I've been married all too long, so perhaps simply take this as an insight about a book I recently reread.

Marriage, according to this particular novel, is about time; about finding time; making time; losing time; savoring time; and yearning for more of it. It is about washing the blood out of your sheets; it is about not minding the yellowed time-stains on a once clean and perfect dress; marriage is about the messy bits more than the pretty ones, because, after the mess has been made, we only cling to each other that much harder.

At the end of the day, marriage is a constant losing of the other, for spaces and fragments, one or the other is gone for a day, sometimes for a week; not literally gone like Henry, but emotionally, mentally missing.

Marriage is about finding your way to each other, again, and again, and again.

Sometimes it feels like there is never enough time, like there is always something in the way, keeping you from one another; always another red drop in each new bowl you pour.

But the world is never as still and perfect as when you find your way back; when the space between two people suddenly falls away and all the worries melt from your mind.

I

suppose the real truth is that I, like Clare, did not think that once I

had him I would still spend so much time trying to find my way back to

him again. I did not think that so many date nights would be canceled; that we would agree to do our own

thing most nights. I did not think I would spend so much time waiting

for him to come to bed. For us, neither of us needed to be a time

traveler for time to keep us apart.

My, oh my, marriage can be complicated. But sometimes, every once in a while, it is the most simple thing in the world.

It just takes a little washing and a little time.

But that's why you promise a lifetime, I guess. And him and I, we still have it all ahead of us.

I for one will make the time to get back to him every day for the rest of my life.