(While I try to refrain from discussing plot points specifically, spoilers lie beyond this point. Please, go no further if you do not wish to uncover the plot of the first Mistborn novel!)

I discovered fantasy writer Brandon Sanderson in the ninth grade by route of the Mistborn trilogy. Back then I spent many a lunch hour perusing the shelves of the library, pulling out book after book and imagining that perhaps someday I might read them all.

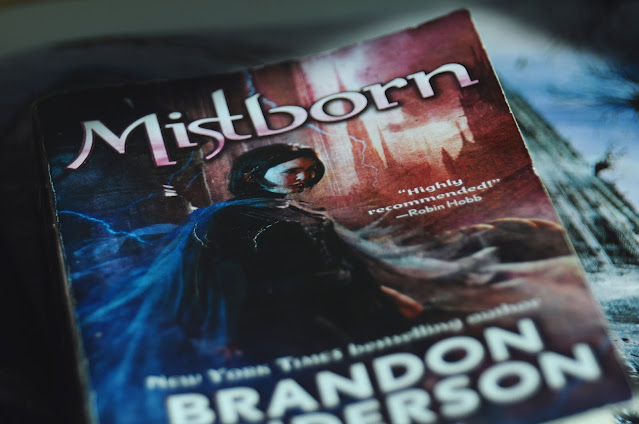

So, on one dark and fateful day, I pulled a paperback off the bottom shelf and was immediately intrigued.

I remember it was the cover that first attracted me to the book. On it Vin (the protagonist) is truly a force to behold, the look in her eye can tell you that much. She is young, intelligent, fierce, and beautiful, and extremely powerful.

While I certainly wasn't new to fantasy at the time, having read The Lord of the Rings two years prior as well as The Inheritance Cycle, this was the first book of this variety that I had ever read. It was Sanderson that made me realize that The Inheritance Cycle wasn't nearly as good as I had once believed. It merely offered a good medium, a stepping stone from children's fairy tales and young adult adventures to the epic and more adult fantasy genre.

One can credit Tolkien with effectively reinventing the legendary and truly terrible Dark Lord, pulling them straight out of old epics, the dark seas where they had so long lain comatose, and reawakening them into the fantasy genre. Christopher Paolini certainly gave it a good try. But it was Sanderson, I believe, who left us with a Dark Lord of truly devastating disposition. Little more than a shadow for most of the tale, Sanderson's Dark Lord lingers like an overpowering presence from the story's dark beginning.

I must admit, reading Mistborn for the first time was an utterly overwhelming experience. While I had been familiar with The Lord of the Rings prior to reading it, it being like a family heirloom in our household, Mistborn was wildly unknown and totally alien. I had no idea what to expect of it. The complexity of Sanderson's magic systems was fully new to me, as was this style of world building. It was, at the time, astoundingly staggering.

These feelings of suffocation served the plot remarkably well. The sense that I was engulfed in this new dark world made it that much more effective and terrifying. I felt like Vin, a girl in front of a hugely hopeless task, the scale of which I had never seen surmounted and had no reason to believe could succeed.

I confess, some of the images the book gave me still haunt me, though I did not realize it until I recognized its shadows in my own mist-filled fictions. The sickening pollution of a world in which skies rain ash; the cruel light of a harsh red sun; the suffocating mists permeated by peasant's superstitions, inhabited by corpse harvesting monsters: I could practically smell the stench and spoliation. It felt sickening and overwhelmingly heavy in a way that made it hard to breathe. I remember feeling my skin crawl when the spike pierced head of an Inquisitor turned in Vin's direction. I remember feeling bereaved and disturbed when the once familiar face of the contemplative and dependable brother returned to us at the end of the book, his eyes pierced inside his skull.

I remember all these things like one remembers the stench of a place even after one leaves it. Most of all, I remember the cloud of depression that came with it.

It has been almost ten years since my first reading of the trilogy, and a reread has been a long time coming. The series holds up incredibly, and though I had long believed that The Stormlight Archive was my favourite of Sanderson's series, now I am no longer so sure.

Mistborn has been with me longer, after all. The images have stayed with me from the ninth grade and on. I remember them so much more vividly than the plot itself, just like I remember the feeling of despair that oozes like a black fog from between its pages.

The book describes this feeling subtly, incorporating it into the details of the world and the suffering in the backdrops; until, that is, the Lord Ruler shows up. It is by his presence that one begins to suspect exactly where this feeling of hopelessness and depression comes from. The Lord Ruler, an immortal emperor who has ruled, polluted, and impoverished this world for hundreds of years, uses his unquenchable powers in Allomancy to suppress anyone near him. His haunting and imposing keep sits over the city, the very shadow of depression, forcing all to be submissive under his despotism. He is the source of their devastation, and thus, it bleeds out from the book, stark and black!

This feeling was so consistent and horrifying throughout the book that it lingered and could be brought up by the mere thought of the novel even long after I had read it. Years later I heard Sanderson compare Mistborn to a version of The Lord of the Rings in which Frodo comes to Mordor, tired, broken, and devastated by his burden, only to find Dark Lord waiting for him at the gates, thanking him for bringing the ring all this way to him. I could not help but laugh, but not because it was funny; only because it was true. Deep down, the hopelessness and manipulation of it still disturbed me.

Why did you think you could ever succeed, these words suggest.

I can still hear the Lord Ruler's voice hissing pitifully: You don't know what I do for mankind. I (am) your god...

Having now finished rereading the first of the Mistborn books, something came to me: an idea that served to add an even greater sense of tragedy to an already dark book.

Before the end, the novel offers us an explanation for the Lord Ruler's extreme power, saying he had the source of both Allomancy and a Feruchemist at his disposal. This, the book explains, is how he had stayed young for so many years, for by storing his youth and his strength in his metals and later burning it, he could use those to the extreme, exaggerating them to the point of exhaustion. Indeed, the image of the Lord Ruler in his old and frail form is no less vivid to me than the young handsome man who arrives to attend mass executions in a black carriage, dressed in black, serving death to hundreds without a flinch.

One is reminded of the effects of the One Ring, which stretches one out till one becomes a horror, a shadow of one's old self. In the same way, the Lord Ruler's powers eat away at him, harvesting from his human flaws of aging and weakness, taking from his fatal feelings and stretching them out into vast, horrid shapes.

It was only on my second read through that I looked past this shadow of despair and depression and saw another sad form behind the Lord Ruler's black figure.

The book doesn't explain the Lord Ruler's overwhelming ability to bring feelings of depravity upon hundreds of people, managing even to pierce those who are meant to be resistant to those forces. He manages to soothe entire crowds into feelings of misery and hopelessness. Yet the explanation is there, beneath the surface of the Lord Ruler's horrid disposition and Sazed's uncertain words: for if things like knowledge, and sight, and age can be stored and burnt and harvested, can depression not be also?

Why not tether your own despondency to your stores; shackle it to your metals and burn them like a power; thrust them out across your subjects to subdue them; dish out your own despair so you can suffocate them in your misery; suppress them under the weight of your own sorrow.

I cannot say that I have forgotten about corpse-devouring mistwraiths and cold men with metal for eyes, but another image lingers now as I finish reading Mistborn for the second time: that of a dark castle over an ash covered city, its people retching on pollution and poverty, submissive in its shadow; and locked away inside this haunted keep, gone from sight and knowledge, an immortal lord deemed god sits in his tower, binding his own despair into vast stores, enough to depress and rule a world for generations.

Inevitably, I leave this world now feeling no less overpowered than I did before. I only understand it better.